Incident Handling Process

This section will cover the incident handling process.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Incident Response Life Cycle

- Preparation Stage

- Preparation - Pre-requisites

- Preparation - Protective Measures

- DMARC

- Endpoint Hardening

- Network Protection

- Privilege Identity Management, MFA, and Passwords

- Vulnerability Scanning and Security Assessments

- User Awareness Training

- Purple Team Exercises

- Detection and Analysis Stage

- Initial Investigation

- Main Investigation

- Creation and Usage of Indicators of Compromise

- Identifying New leads and Impacted Systems

- Data Collection and Analysis

- Containment, Eradication, and Recovery Stage

- Containment

- Eradication

- Recovery

- Post-Incident Activity Stage

Introduction

Like the Cyber Kill Chain, there are also processes and different stages when responding to an incident. This is defined as the incident handling process. The incident handling process defines a capability for organisations to prepare, detect, and respond to malicious events.

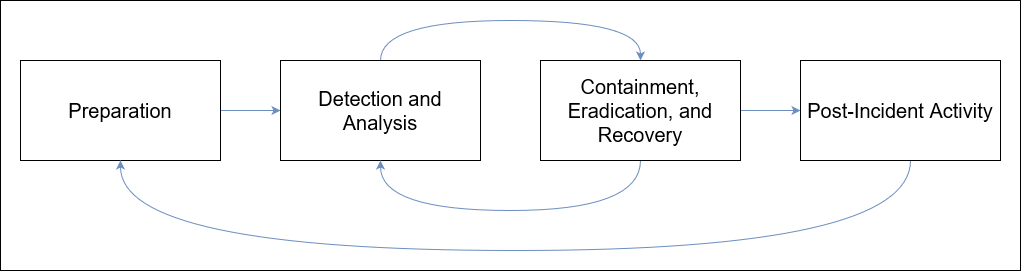

An example of this will be the Incident Response Life Cycle by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST).

The document can be found at the following link. This section will be focusing on "Handling an Incident" on page 21.

https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/specialpublications/nist.sp.800-61r2.pdf

Incident Response Life Cycle

There are four (4) distinct stages in the Incident Response Framework.

Incident handlers spend most of their time in the first two stages, the preparation and detection and analysis stage. In these stages, this is where we spend a lot of time improving ourselves and looking for the next malicious event.

When a malicious event is detected, we then move onto the next stage and respond to it. Note that there should always be resources constantly operating on the first two stages to avoid disruption of preparation and detection capabilities.

There are two main activities for incident handling. They are investigating and recovering. The investigation aims are:

- Discover the initial "patient zero" victim and create an (ongoing if still active) incident timeline.

- Determine the tools and malware that the adversaries used.

- Document the compromised systems and what the adversaries done.

Once the investigation is done, the recovery activity involves creating and implementing a recovery plan. Once the plan is implemented, the business should resume normal business operations if the incident caused any disruptions.

When an incident is fully handled, a report will be created and issued that can include items such as the cause and cost of the incident and any lessons learned during the handling process to prevent similar incidents from happening in the future.

Preparation Stage

There are two objectives in the preparation stage:

- Establishment of incident handling capability within the organisation.

- Protect against and prevent IT security incidents by implementing appropriate protective measures.

Some examples of protective measures can be endpoint and server hardening, Active Directory tiering, multi-factor authentication, privileged access management (PAM), and more.

While protecting against incidents is not the responsibility of the incident handling team, this activity is fundamental to the overall success.

Preparation - Pre-requisites

In this stage, we will need to ensure that we have the following:

- Skilled incident handling team members.

- Trained workforce.

- Clear policies and documentation.

- Tools (software and hardware).

The policies and documentation should be kept up-to-date and contain some of the following:

- Contact information and roles of the incident handling team members.

- Contact information for legal and compliance department, management, IT support, public relations team, law enforcement, internet service provider, facility management, and incident response team.

- Incident response policy, plan, and procedures.

- Incident information sharing policy and procedures.

- Baseline of systems and networks using a clean state environment.

- Network diagrams.

- Organisation-wide asset management database.

- User accounts with excessive privileges that can be used on-demand by the team when necessary.

- Ability to acquire hardware, software, or an external resource without a complete procurement process in urgent situations.

- Forensic/Investigative cheat sheets

Depending on the incident, it can be handled relatively quickly without much issue or require external parties such as law enforcement or informing clients and third-party vendors.

Some tools that can be used includes but not limited to:

- Additional laptops/workstations for forensics work.

- Digital forensic image acquisition and analysis tools.

- Memory capture and analysis tools.

- Live response capture and analysis tools.

- Log analysis tools.

- Network capture and analysis tools.

- Storage such as hard drives.

- Templates and forms such as indicator of compromise (IoC) creator and chain of custody forms.

Preparation - Protective Measures

This section will cover some highly recommended protective measures for different scenarios and items.

The following will be covered here:

- DMARC

- Endpoint Hardening

- Network Protection

- Privilege Identity Management, MFA, and Passwords

- Vulnerability Scanning

- User Awareness Training

- Purple Team Exercises

DMARC

DMARC is an email protection that is built on top of existing SPF and DKIM. The goal behind DMARC is to reject emails that are spoofed or "pretend" to originate from your organisation.

An example will be where an attacker attempts to use your domain to conduct a phishing exercise via email but when sent, the system will reject the email before it reaches the intended recipient.

Endpoint Hardening

Endpoints can be devices and machines such as workstations, laptops, printers, etc. These are entry points for most attacks that are faced daily.

Some important actions to note includes but not limited to:

- Disabling LLMNR/NetBIOS.

- Implement LAPS and remove administrative privileges from regular users.

- Use the principle of least privilege.

- Disable or configure PowerShell in "ConstrainedLanguage" mode.

- Utilise host-based firewalls.

- Deploy an EDR product.

Network Protection

Some protective implementations at the network level can be network segmentation. This is where there are multiple, smaller networks instead of a large, flat network. This allows more granular control especially when it comes to firewall rules.

An example will be having a network for user devices, a server network for critical systems, and a DMZ for machines that are exposed to the internet.

Additional implementations can be having a IPS/IDS system and 802.1x.

Privilege Identity Management, MFA, and Passwords

Implement a strong password policies and have multi-factor authentication in place. Additional items can be having PAM systems for high privileged accounts.

Vulnerability Scanning and Security Assessments

Performing vulnerability scans on a regular basis can uncover potential vulnerabilities and have them fixed before an incident happen.

Performing security assessments on the network such as Active Directory on a regular basis can uncover potential vulnerabilities and misconfigurations.

User Awareness Training

Training users will allow them to recognise suspicious behaviour and have it reported before an incident happens. While it is unlikely to be 100% successful here, it is known to significantly reduce the number of successful compromises.

Periodic "surprise" tests should be conducted to assess if the training is effective. This can include a mock phishing exercise or having USB sticks dropped in the building randomly.

Purple Team Exercises

Having incident handlers and other relevant personnel engaged can help identify vulnerabilities, current defensive capability, and any weak spots in the organisation.

For any threat that is undetected, there is room for improvement. For every detected threat, items such as playbooks and incident handling procedures can be created and improved on to ensure that they are robust and can achieve the expected result.

Detection and Analysis Stage

This stage involves all aspects of detecting an incident such as using sensors, logs, and more. It also includes information and knowledge sharing, as well as utilising context-based threat intelligence.

Threats can be introduced to the organisation via an infinite amount of attack vectors. Their detection can come from sources such as:

- An employee noticing abnormal behaviour.

- An alert from tools such as an EDR, firewall, IDS, SIEM, etc.

- Threat hunting activities.

- A third-party notification that signs of a compromised have been detected.

It is recommended to create levels of detection by logically categorising the network:

- Detection at the network parameter (using firewalls, internet-facing network intrusion detection/prevention systems, DMZ, etc.)

- Detection at the internal network level (using local firewalls, host intrusion detection/prevention systems, etc.)

- Detection at the endpoint level (using anti-virus, endpoint detection and response systems, etc.)

- Detection at the application level (using application logs, service logs, etc.)

Initial Investigation

When a security incident is detected, some initial investigation should be conducted to establish context before assembling a team and calling an organisation-wide incident response.

We should aim to collect as much information as possible at this stage about the following:

- Date and time when the incident was reported. Additionally, who detected and/or reported the incident.

- How was the incident detected?

- What is the incident?

- A list of impacted systems if relevant.

- Document who had accessed the impacted systems and the actions taken. Make a note if it is an on-going incident or if the suspicious activity has been stopped.

- Document the physical location, operating system information, IP addresses, hostnames, system owner, system purpose, and current state of the system.

- If malware is involved, list of IP addresses, time and date of detection, type of malware, systems impacted, export of malicious files with forensics information such as hashes, copies of files, etc.

Once the relevant information has been collected, a timeline can be created to keep us organised and informed throughout the event to provide an overall picture of what happened.

The timeline should include information such as date, time of event, hostname, event description, data source, and more if necessary.

We should also ask ourselves some questions to get an idea of the incident severity and extent:

- What is the exploitation impact?

- What are the exploitation requirements?

- Are there/is it possible for any business-critical systems to be affected?

- Are there any remediation steps?

- How many systems have been impacted?

- Is the exploit being used in the wild?

- Does the exploit have any worm-like capabilities (Self-replicating, etc.)?

Incidents can also be a confidential and sensitive topic. As such, all information gathered should be kept on a need-to-know basis, unless applicable laws or a management decision instruct us otherwise.

Main Investigation

When an investigation is started, the aim is to understand what and how it happened. To analyse the data collected from the incident properly and efficiently, it is important to have deep technical knowledge and experience in the field.

If we do not know how an incident happened or what was impacted, any remediation steps taken will not be able to ensure that such an incident will not happen again.

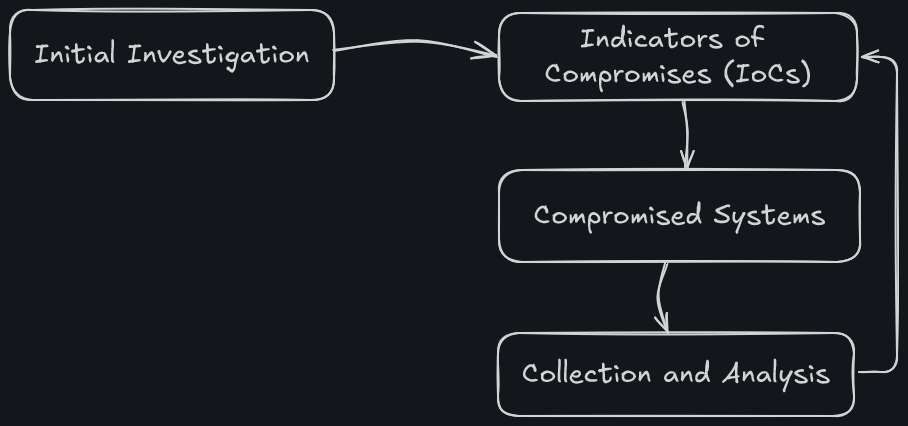

During the investigation, we can begin a 3-step process that will iterate over and over again as the investigation evolves. The process includes:

- Creation and usage of indicators of compromise (IoC)

- Identification of new leads and impacted systems

- Data collection and analysis from the new leads and impacted system.

To reach a conclusion, an investigation should be based on valid leads that have been discovered throughout the entire investigation process. New needs should always be brought up and investigated instead of narrowing down to a specific activity in order to gain a full overview of the impact.

Creation and Usage of Indicators of Compromise

Indicators of Compromise (IoC) are signs that an incident has occurred. IOCs are documented in a structured manner, which represents the artefacts of the compromise.

Some examples of IOCs can be an IP address, hash values for files, file names, and more. As IOCs are a very important part of an investigation, tools and special languages such as OpenIOC has been developed to document and share them in a standardise manner. Another widely use standard for IOCs is Yara.

Some tools that can be used are:

- OpenIOC

- Yara

- Mandiant's IOC Editor

To leverage IOCs, the deployment of IOC-obtaining/searching tools that are native or third-party can be used. A common approach is to use WMI or PowerShell for IOC-related operations in Windows.

During an investigation, it is important to prevent high privileged account credentials from being cached when connecting to a potentially compromised/compromised system.

Identifying New Leads and Impacted Systems

After searching for IOCs, it is expected to have some hits that reveal other systems with the same signs of compromise. The hits may not be directly related or associated with the incident as sometimes the IOC can be too generic. Hence, we will need to identify and eliminate false positives and tune the IOC if necessary.

Data Collection and Analysis

Once the compromised systems have been identified using items such as IOCs, we will want to collect and preserve the state of those systems for further analysis.

Depending on the system and incident, there are multiple ways to how and what data to collect. An example will be where we want to perform "live response" on a system as it is running. In other cases, we may want to shutdown and perform analysis on it.

A "live response" is common as it allows us to collect a predefined set of data that may explain what happened in a system. Such artefacts may only live within volatile memory parts such as RAM, which will be lost when the machine is turned off.

Do note that a chain of custody should be recorded if legal action is required and to keep note of who has accessed and handled the data.

Containment, Eradication, and Recovery Stage

In this stage, the investigation is completed and the type of incident and the impact has been understood. The goal of this stage is to prevent the incident from causing more damage.

Containment

This part is where actions are taken to prevent the spread of the incident. The actions can be divided into short-term containment and long-term containment.

It is important the containment actions are coordinated and executed across all systems simultaneously to reduce the risk of notifying the attackers that we are after them. This may cause them to change their techniques and tools to persist in the environment.

In short-term containment, the actions taken leaves a minimal footprint on the systems. Some examples of these actions are placing the system into a separate or isolated VLAN, disconnecting the system from the network. This will allow more time to develop a more permanent remediation strategy.

In long-term containment, the actions focus on persisting actions and changes. Some examples of these actions are changing user passwords, applying firewall rules, deploying host-based intrusion detection systems, applying patches, or shutting down systems.

Eradication

Once the incident is contained, eradication is needed to eliminate the root cause of the incident and what is left of it to ensure that the adversary is out of the network and systems.

Some activities that can be taken here are removing the malware, rebuilding or reimaging the systems, or restoring from backups. Additional system hardening measures can also be performed in this stage.

Recovery

The recovery stage is where systems are brought back to normal operations. All restored systems will be monitored closely after the incident as previously compromised systems tend to be targets again if the adversary regains access to the environment.

Some examples of suspicious events to monitor are:

- Unusual logons

- Unusual processes

- Changes to critical systems and places such as the registry.

Post-Incident Activity Stage

In this stage, the objective is to document the incident and improve our capabilities based on the lessons learnt.

The final report is a crucial part of the entire process. It can contain answers to questions such as:

- What, how, and when did it happen?

- Performance of the team when dealing with the incident.

- Did the business provide enough and necessary information and respond swiftly to aid in handling the incident in an efficient manner?

- What can be done to improve?

- What preventive measures, tools, and resources can be used to prevent similar incidents in the future?

Such reports can act as a reference for future events that are similar and provide us knowledge of how it was handled.